For those who were unable to make it to this year’s Clothiers event, here are the examples I brought to share for the Japanese display. They are a couple of garments that I had made, plus a few panels of vintage (1940s-1960s) kimono panels that showed modern examples of some dyeing techniques that were used in pre-Edo Japan. Of course, the motifs are smaller on these modern pieces but they show the complexity of these simple garments. Note: the panels are from damaged vintage kimono that I had taken apart to reuse the silk for other projects.

Pink Brocade Uchikake, photo by Jay Reynolds

Item: Pink Brocade Uchikake Kosode 打掛小袖

Time: Muromachi Era (1336-1573)

Place: Japan

Owner: Ki no Kotori

Made by: Ki no Kotori

Points of Interest: This piece is a kosode (small-sleeved garment) uchikake. The sleeves are smaller and the panels are wider than that of a modern kimono. The average width of a kimono panel is between 12-14 inches, while kosode panels were 17-18 inches wide. During the 17th century, the kosode evolved into the kimono, becoming longer and narrower, with larger sleeves and an altered neckline. The obi (belt) that held the garment in place also evolved from a simple narrow belt to an intricately woven band that covered most of the abdomen.

This modern Chinese brocade is similar to the ornate style of brocade favored in the Muromachi Era. The uchikake is meant to be worn open above another kosode (or two—they were often layered, especially in the colder months). Uchikake were always lined. They are still in use today as bridal garments.

This is an earlier piece of mine, made in 2003-2004. There are a few things I would do differently now, especially with padding the bottom of the lining. The materials are modern, but I got them at a clearance sale for a very affordable price and while I did have to change some of the sewing (tighter stitches because Lordy, this stuff frays like crazy!), I think it gives a good approximation of what the garment should look like.

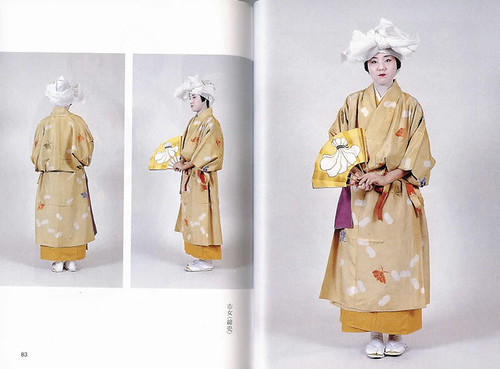

Leaf Kosode, photo courtesy of Jay Reynolds

Item: Autumn Leaf Kosode小袖

Time: Azuchi-Momoyama Era (1573-1600)

Place: Japan

Owner: Ki no Kotori

Made by: Ki no Kotori

Points of Interest: This piece is an unlined kosode (small-sleeved garment) that was made by altering a vintage meisen silk kimono. I chose this kimono to alter because of the large pattern, which is similar to what would have been worn before 1600. The silk is probably a silk/poly blend. The original kimono probably dates from the 1950’s. Meisen silk is a kasuri (ikat) weave where the design is stenciled on the warp and then woven in. It was extremely popular from the 1920’s until the 1960’s. The Kasuri technique does date back into the middle ages, although it didn’t become widely used until the Edo period (1603-1868).

The sleeves are slightly larger than a true kosode because I wanted to show off the leaf pattern on them. I added strips of a scrap piece of rayon to widen the garment. The rayon I had was too short and so I had to piece it at the bottom. I also had to put in a wide hem as the original kimono was a bit too long. There are several late-period examples of pieced kosode, although usually using horizontal rather than vertical lines. The original garment was unlined, so I kept it that way. By adapting the vintage kimono and using the scrap rayon (left over from another project), I kept the price of the project down to about $30.

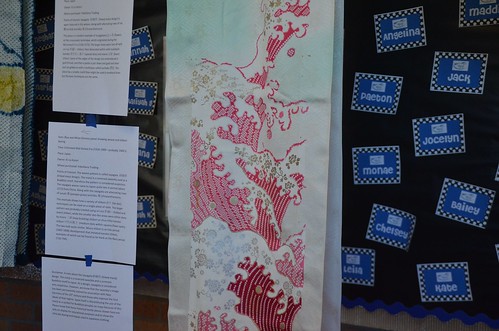

Multi-colored Vintage Kimono Panel (on right of photo), photo courtesy of Edward Hauschild

Item: Multi-colored Vintage Kimono Panel

Time: Estimated Mid-Showa Era (1926-1989—probably 1940’s)

Place: Japan

Owner: Ki no Kotori

Where purchased: YokoDana Trading

Points of Interest: This piece is an example of somewake 染分 (using various colors) dyeing, a technique first used during the Kamakura Era (1185-1333). The earliest extant example of this technique is a drawing of a woman from 1309.

Blue Shibori Example, photo by Edward Hauschild

Blue Shibori Example, Detail showing Sayagata weave and Kanoko dots

Item: Blue and White Kimono panel showing weave and shibori dyeing

Time: Estimated Mid-Showa Era (1926-1989—probably 1960’s)

Place: Japan

Owner: Ki no Kotori

Where purchased: YokoDana Trading

Points of Interest: The weave pattern is called sayagata 紗綾形 (linked manji design). The manji is a reversed swastika used as a Buddhist motif, therefore the pattern is considered auspicious. The sayagata weave came to Japan quite late in period (about 1573) from China. Along with the sayagata are alternating rows of susuki 薄 (pampas grass) and kiku 菊 (chrysanthemum).

This example shows how a variety of shibori 絞り (tie-dye) techniques can be used on a single piece of cloth. The larger pattern was probably created using ori-nui 折縫い (folded and sewn) shibori, while the smaller dot-like areas were either done by miura 三浦 (loop braiding) shibori or chuu-hitta kanoko shibori 中匹田鹿子 (medium dots within squares/fawn spots). The two look quite similar. Miura shibori is an Edo period (1603-1868) development that imitated kanoko shibori, examples of which can be found as far back as the Nara period (710-794).

Pink Tsujigahana Example, photo by Edward Hauschild

Detail of Pink Tsujigahana Example, photo courtesy of Edward Hauschild

Detail showing sayagata weave and closer view of the dye details

Item: Kimono Panel Showing Tsujigahana Techniques

Time: Estimated Mid-Showa Era (1926-1989—probably 1960’s)

Place: Japan

Owner: Ki no Kotori

Where purchased: YokoDana Trading

Points of Interest: Sayagata 紗綾形 (linked manji design) is again featured in this weave, along with alternating rows of ran 蘭 (orchid) and kiku 菊 (chrysanthemum).

This piece is a modern example of tsujigahana 辻ヶ花 (flowers at the crossroads) technique, which originated during the Muromachi Era (1336-1573). The larger areas were tied off with ori-nui 折縫い shibori, then decorated within with tsukidashi kanoko 突き出し鹿子 (spaced dots) and mame 豆絞 (bean) shibori. Some of the edges of the design are embroidered in gold thread, and then a paste is put down and gold and silver leaf are gilded on with a technique called surihaku 摺箔.This piece has a smaller motif than might be used in medieval times but the basic techniques are the same.

Disclaimer: A note about the Sayagata 紗綾形 (linked manji) design. The manji is a reversed swastika and a common Buddhist motif in Japan. As a design, sayagata is considered very auspicious. However, we know that the swastika’s image has been permanently stained by association with Nazi Germany of the 20th century and those who espouse the foul ideals of that regime. Japan itself is discontinuing the use of the manji as a symbol for Buddhist temples on maps because of this. Please know that these historical textile pieces shown here are only on display for educational purposes and to show the intricate dyeing techniques used in Japanese clothing.

YokoDana Trading is a company that sells vintage kimono in bulk, usually as “cutters” for craft projects (quilting, for example) at a very reasonable price. Sometimes there will be kimono included that are in wearable shape, but need to be taken apart for cleaning. Another vendor that I would recommend is Ohio Kimono. The owner has been involved in the SCA and can recommend garments that have more medieval motifs. I’ve gotten a few kimono from her that I have adapted for SCA wear.