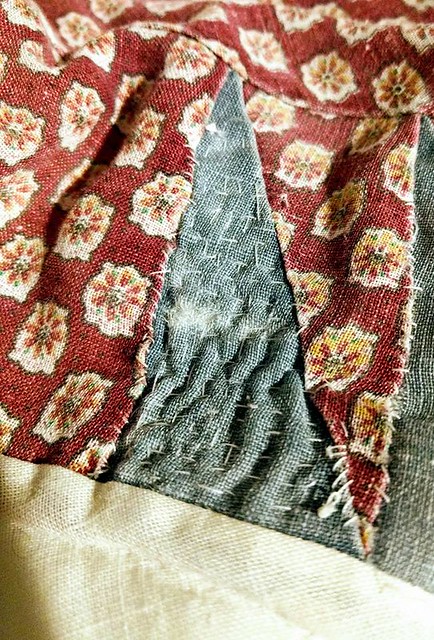

The canvas-weight shibori patterned material that I am taking apart to repurpose. Tried to make a kosode from it, but it is too thick and scratchy, and lining it would make it too warm. So it will be made into something else, probably some kind of carrying bags. I got the material cheap when Hancock’s went out of business, $11 for 9 yards.

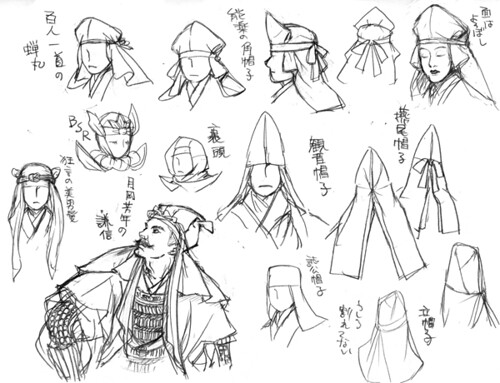

Day 4 of 100 Days of Arts and Sciences. Soprano recorder practice, more on the kanji radicals workbook, shodo practice, pulled together some of my Japanese doll research to answer a question on SCA Japanese FB page.

Day 5 of 100 Days of Arts and Sciences. Practiced tenor recorder, wrote a couple of tanka, did some Japanese clothing research.

Day 6 of 100 Days of Arts and Sciences. Practiced soprano recorder, went to Shodo lesson, made progress on Class prep for RUSH, fell down research hole about how lower-class Japanese patched/repaired clothing. Mostly 19th and early 20th century information, but can certainly tie literary references to the practice (regrettably vague), but some Shōsō-in garments show this kind of patching or similar. Worth digging more into. Next few days will be slow, have some Real Life constraints on my time, but should be able to do something, even small!

Day 7 of 100 Days of Arts and Sciences. Nursing a migraine today, so just did some hand-sewing repair on a cloak and some zukin where threads had come loose. Took apart a trial kosode I made from some shibori-designed fabric I picked up on clearance when Hancock’s closed. Thought it might work for garb. It looks right but it is almost canvas weight and would be too hot and scratchy. Will probably repurpose the material to make bags or something like that instead. Waste not, want not.

First attempt at using Japanese boro stitching technique to fix a frayed area on a quilt. Simple running stitch used in period. Not complete success. Need more even stitches, probably slap a patch over the area and then try running stitch and see how that goes. Just experimenting on an idea.

Day 8 of 100 Days of Arts and Sciences. Wrote two tanka and a haiku, more reading on Japanese work clothes, soprano recorder practice, sourcing materials for my RUSH classes (and trying to remember where I stashed those student brushes–I’ve given some away but I know I have more.) I need to fit in some time tomorrow to get that kosode sloper put together so I can see if my updated pattern works. #somedayiwillbeorganized #todayisnotthatday

Day 9 of 100 Days of Arts and Sciences. Still gathering materials for RUSH classes, continued reading book on Japanese work clothes, and taking apart failed canvas shibori kosode to reuse material.

Day 10 of 100 Days of Arts and Sciences. Updated SCA blog, finished reading book on Japanese work clothes, finished taking apart shibori kosode (fabric will be stored an be reworked into carrying bags later, after I get more clothing sewn!).

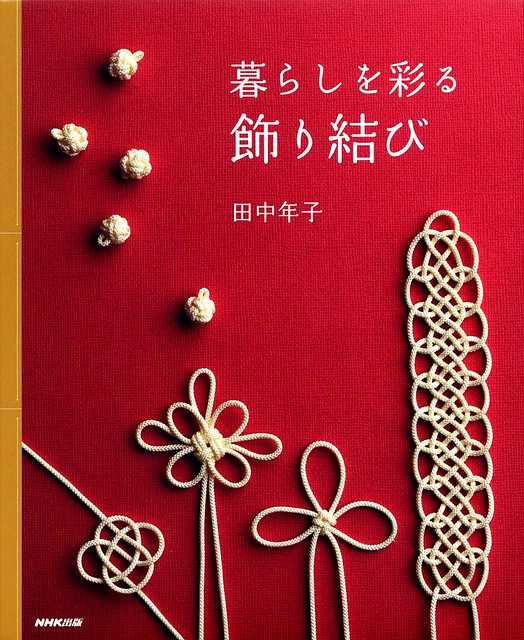

The book I’ve been reading about Japanese work clothes is Stories Clothes Tell: Voices of Working Class Japan by Horikiri Tatsuichi, translated by Reiko Wagoner. ISBN 1442265108 (ISBN13: 9781442265103). The author spent decades traveling around Japan and collecting examples of working-class clothing, mostly from the Meiji, Taisho, and early Showa era. (So he focused roughly 1868 to the early 1960’s in time period.) This book is a translation of several essays that Horikiri wrote concerning items from this collection. While he tends to go a little far in conjecture about items, the small details about these work clothes and how they were used is a fascinating read, if a bit melancholy since some of these stories really bring into focus how desperately poor these people were.

There are more “social histories” now than there used to be, that focus on the lives of the common people. Since the time period this book focused on was post-1600, many items he discussed were not exactly applicable to SCA, but his approach is certainly one we can apply. It was remarkable to see how slowly the clothing evolved in usage–Horikiri discusses the evolution of some of the items from Edo-period clothing. With a little work, some items might be placed before that. It would take looking at visual sources and perhaps literature, since no extant pieces would exist.

The book was also useful in isolating some Japanese terms regarding fabric and clothing and includes a glossary, although most of the items mentioned are Edo-period or later. Still, there is some hidden treasure here. In one essay, he speaks of the difference between the rough-woven asa 大麻(hemp) cloth used by the lower classes, and the finer-woven joufu 上布, which seemed to be linen or perhaps a mix of hemp and linen? Definitely of a much tighter weave, and according to this Japanese wikipedia article on 上布, there are some extant pre-1600 examples of joufu?

Anyway, it looks like it would be worthwhile to track down more of these specific terms, not often referenced in English language sources!

Photographer unknown.

Photographer unknown.