Battling con crud from Worldcon this week. I’m supposed to be doing a translation for someone, but my brain is so fuzzy that I haven’t been able to concentrate, so I’ve been sewing on part of my Queen’s Prize Project, which is on zukin (hoods). I’m doing the sode-zukin (which is the wimple kind of zukin that I did for that paper I wrote years ago), the zukin from The Maple Viewers (and yes, what those ladies are wearing ARE zukin–I’ve found modern variants), a mousu (which looks like a sode-zukin, but are larger) and if I have time, a kato no kesa 裏頭(か[くわ]とう)の袈裟(けさ), which is what the sohei warrior monks wore. The kanji translates as “a kesa worn on the head”. Kesa is a Buddhist religious garment usually worn over kimono as a kind of apron.

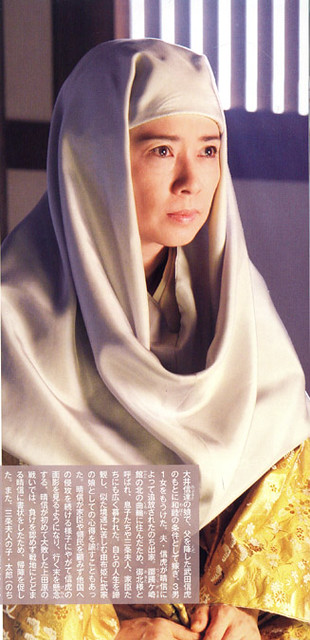

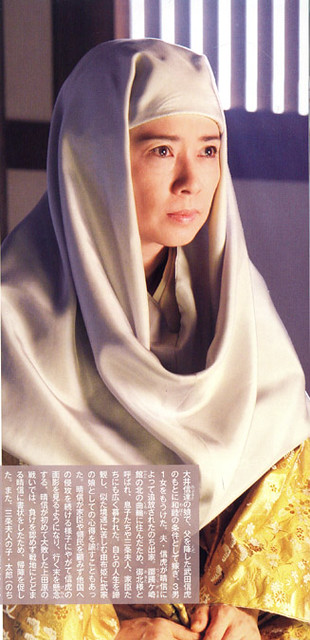

Sode-zukin example from the NHK taiga drama Fuurin Kazan.

I’m really excited about this last one–I kept wondering why I would sometimes see seam lines on what usually looks like just a rectangular white cloth tied around the head. It’s a kesa! And kesa are usually sewn with what is called the rice-field pattern. And THAT explains the seam lines!

From the NHK Drama Yoshitsune, the Warrior Monk Benkei is wearing a Kato no Kesa.

The only thing is I will have to sew like the wind to get the thing done in time and with the pattern, that’s going to be tricky. Plus I still have to write up the information, in a simple format since this is not a literary entry. But I still have almost 3 weeks. I might skip the mousu (which I don’t have as much info about, just an entry from the Japanese Costume Museum) and concentrate on the kato no kesa instead.

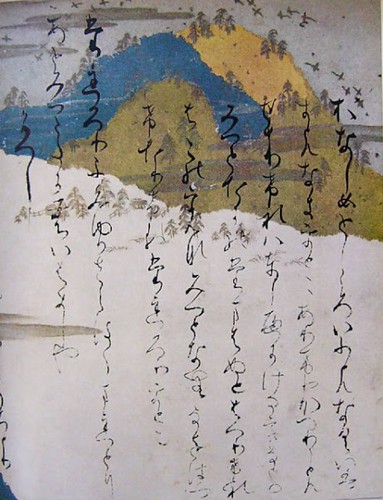

Ingibiorg, who also does Japanese poetry here in Calontir, did a poetry exchange with me this summer and asked if she could enter it as an A&S entry for Cattle Raids (an event up in Lincoln, Nebraska where she lives). We each wrote up explanations about our respective poems and how we took elements from each other in the exchange. I think she was going to present the poems on some marbled paper or something? Anyway, no word as to how that turned out. I hope she got some good feedback, since most people tend to ignore poetry entries.